The series on Aotearoa New Zealand continues here with several articles on Karori Normal School.

The series on Aotearoa New Zealand continues here with several articles on Karori Normal School.

Karori Normal School (KNS) was the first school I visited in New Zealand. (Normal refers to a relationship with a college of education to offer teaching opportunities and mentoring to student teachers.) As always, I arrived early to walk around the neighborhood (although on this very wet and windy day, I landed at a bakery and, after deciding which kind of pie to have for breakfast, had a great conversation about education with some local residents).

As is almost every neighborhood around Wellington, Karori is located up a long and winding road from the central business district. It is a full primary school serving approximately 750 students in grades 1-8 (equivalent to K-7 in the US). The student population — 82% NZ European/Pākehā; 13% Asian; 4% Māori, and 1% Pasifika — are primarily upper income, as Karori is recognized as a Decile 10 school.

A big thanks to Andrea Peetz, Conrad Kelly and Carol Pilcher for taking the time to talk with me about KNS.

Becoming Student-Centered

In 2015, Karori Normal began the journey toward becoming student-centered. Their students were generally doing well academically based on the external assessments used to measure where students were based on the national standards. (See upcoming article How Standards Led to Student-Centered Learning at Karori Normal School.) However, they were concerned that students were not engaged and that they were not finding meaning in their learning. (Please note: There is a general concern in New Zealand about anxiety and teen suicide. The country has the highest suicide rate in OECD nations, with high rates for young Māori and Pasifika young men.) Thus, Karori wanted to put well-being, particularly social and emotional well-being, in the core of their approach. They wanted to become student-centered.

The senior leadership team is enthusiastic about student-centered learning. It takes a balanced leadership strategy to get everyone at KNS going in the same direction to create a shared vision without driving or imposing the vision of student-centeredness. A reference to Māori culture captured the passion and commitment they hold for their vision: The KNS waka (a Māori watercraft) is going in the direction of student-centered and everyone on board needs to be rowing in the same direction.

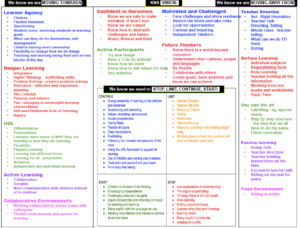

In order to help communicate the vision, the Karori team created a framework that describes the vision, including what they want to do more of and what they want to stop doing. (See below.) The vision is for students to be confident, motivated and challenged, active participants, and future thinkers. This requires attention to learner agency, deeper learning, UDL, active learning, and collaborative environments. They want to move away from teacher-directed, surface learning, one size fits all, passive learning, and fixed environments.

The KNS is constantly asking themselves where they are in the progress toward their vision and how do they know. They keep the focus on the whole child, not just academic progress. There is a shared understanding that if they start with well-being, everything else will fall into place. They know that they can’t always monitor it exactly at all times. However, just the process of asking the question as a team helps to create a common understanding of their progress and where attention is needed.

The Power of UDL for Creating a Student-Centered School

The team at Karori soon came to the conclusion that to be student-centered required intentionality in creating learning experiences for students. They turned to the Universal Designs for Learning framework to create an inclusive, cohesive, student-centered approach. UDL helped them make the shift toward greater learner agency.

The team at Karori soon came to the conclusion that to be student-centered required intentionality in creating learning experiences for students. They turned to the Universal Designs for Learning framework to create an inclusive, cohesive, student-centered approach. UDL helped them make the shift toward greater learner agency.

Every teacher was trained on UDL. Teams were organized, and the training was differentiated for those teams. Afterwards, they came back together to work more deeply on what UDL would mean for their classrooms. The staff worked on one principal at a time. There was lots of unpacking. At the beginning, most of the team thought it was just about choice. When they started to bring in the research about the brain and learning, everyone started to understand the real power of UDL to help learners be the best they can be. Again, keeping a sense of personal ownership among teachers and a shared vision while integrating UDL a schoolwide effort required leadership attention.

UDL was very helpful in changing the mindset at KNS. Before, teachers planned for the middle. With UDL they understand that there are multiple variables in how students learn. By building relationships with students and getting to know them better than ever before, it makes it easier for teachers to play for all the strengths and weaknesses students bring. The teachers at Karori now think about how they can change the environment to create better conditions for student learning. As I toured the school, flexible seating to provide choice and some control over the environment was evident — there were students on the ground, in small teams, in the hallways, and sitting around a table with a teacher.

UDL has powerfully highlighted insights about teaching and assessing that are improving practice at KNS. Here are two that were shared during my visit:

- Identify and question situations in which teachers know (or believe) a student is going to fail. Are those situations needed at all and, if so, make sure the supports that will help every student be successful are in place.

- Remember that students grow and change as learners. Just because a student may be failing or acting out in one situation doesn’t mean they can’t demonstrate a different set of reactions and behaviors if a situation is created in which they will be successful. The conditions shape how we understand learners, and educators have the power to shape these conditions. The teachers now plan for “predicted variability” from the start.

There was agreement that UDL helps teachers learn more about teaching. Before KNS introduced UDL, they had laid the groundwork for the practice of teaching as inquiry. However, it wasn’t yet part of the core philosophy about teaching. The UDL framework makes it easy to introduce inquiry and reflection as a common part of teacher practice. When they identify a student not progressing, they discover the reasons why and shape an inquiry around it.

UDL has helped KNS create a much more inclusive culture and instructional approach. Perhaps a student has dyslexia or problems with maths (New Zealanders says “maths” rather than “math”), the teachers will read up on the topic and develop strategies that will work for the child. Maybe they need to change the screen overlay being used. Maybe they need to organize more time and more instructional support. However, instead of leaving it as an individual strategy, they then apply it universally to see if it will benefit all learners. Students can have choices over color overlays, and more flexibility in the schedule is organized for any student who needs more help. Teachers are engaged in finding more strategies to help students build up their skills as learners. For example, students can use a “pipe” to talk through to hear themselves think. They read back their writing in their own voice to hear how their writing sounds.

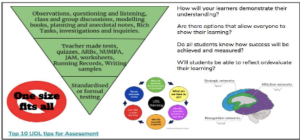

They are in their third year of using UDL and are finding it helps them return to the key principles that are guiding their school. UDL has helped to counteract the rigidity of the national standards initiative that ran from 2010-2017. Karori keeps observations about student learning at the top of the framework they use to stay focused on multiple measures. Data on standardized assessments are at the bottom. At KNS, educators and the leadership team are constantly asking themselves what a practice or activity means for engagement, for learning, for how they are going to teach. The challenge for leadership is to find the ‘through line’ that creates cohesiveness. They are constantly slicing the curriculum and examining it. What does it mean for teachers, students, parents? KNS hasn’t done it alone. Chrissie Butler and Linda Ojala from CORE and Bek Galloway, an education consultant, have all been helpful along the way.

Karori is now applying UDL to everything in the school, including staff meetings and parent communication. In fact, they are using the UDL framework to look at how they organize and prepare reporting to parents on student growth. They also noted that as the student-centered school culture increases, bullying is on the decrease. UDL has become the framework at KNS upon which everything hangs.

Supporting Teachers in a Student-Centered School

New Zealand’s initial teacher education (ITE or pre-service) is very similar to that of the US. The majority of first-time teachers have three years of study of education and a 14-week practicum. Initial teacher education tends to be almost all theory. Teachers know about and have studied the key documents that shape our education system, such as the National Curriculum. However, they haven’t had extensive opportunity to apply it. Just as in the US, new teachers are novices in the craft of teaching. New Zealand has a two-year provisional period before teachers can register with the Teaching Council (previously the Education Council). During this two years, Karori provides new teachers with mentors, core issues of instruction and assessment, and ongoing support.

Every teacher has two days’ release from classrooms per term (there is a national school calendar with four terms per year) to visit other classrooms, meet with students and parents, or pursue improvements in their practice. Teaching as inquiry is part of the National Curriculum and provides guidance that professional learning should be rooted in the actual experiences of teachers helping students learn.

Schools and teachers use a variety of practices in their teaching as inquiry, with some of them adding little value. Karori has chosen to use the practice analysis conversation developed by Helen Timperley. When a teacher decides they want help with their practice, they ask another teacher to interview five or six of the students in their class for about five minutes each. The interviewing teacher asks students questions such as, “How did the teacher help you? How did he or she help you be successful? What types of decisions did you make about your learning? What could the teacher do next to help you?” The feedback is brought to the teacher, followed by a discussion about where they might strengthen their practice. The practice analysis conversation is paying off at KNS. It’s now being formalized with once-a-year observations from one member of the senior leadership team and one other teacher.

Teachers have one meeting per week to work together. Otherwise, collaborative time has to be found at lunch or the holidays between terms. However, there is a daily activity that supports collegiality in schools. At Karori, as at every school I visited, teachers all gathered at some point in the morning for tea. Announcements were held to a bare minimum, with the time reserved for letting down for a bit and catching up with colleagues. Tea time is trust-building time.

At Karori, teachers have a great deal of autonomy within the guardrails of the curriculum levels. Teachers can use whatever tools or frameworks they want to think about how students are learning and progressing.Teachers may use Debono’s thinking hats to encourage students to be creative, Bloom’s to describe depth of the learning, or SOLO to describe progress in thinking. This can obviously be a stretch for new teachers. Thus, they receive plenty of support in developing learning experiences.